There has been intense concern and discussion about the Almajiri system, a traditional Islamic educational system common in Northern Nigeria. The system, which had its origins in the quest for Quranic education, was intended to teach young boys religious knowledge and discipline. They are transported far from home to study under Islamic teachers.

But over time, the system has drawn more criticism because of its links to street begging, child exploitation, and limited access to formal secular education.

The problems with the Almajiri system persist even after bold initiatives by previous governments to correct them.

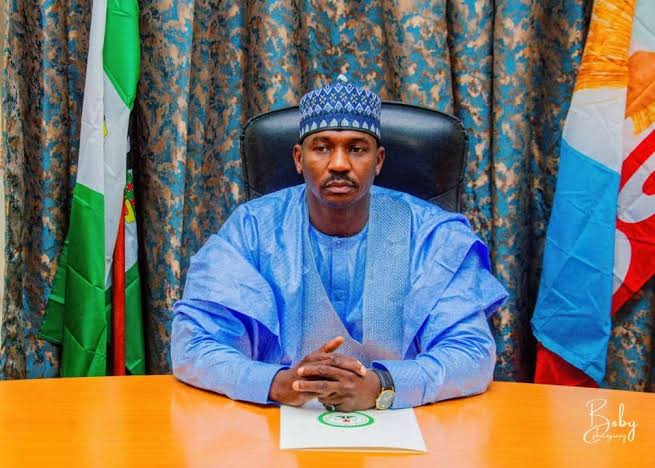

It is, therefore, imperative that Sokoto State, as the headquarters of Islam in Nigeria, should take the lead in the reformation of Islamic education system. Governor Ahmad Aliyu has taken the bull by the horn, as he implements smart, long-lasting, and culturally aware reforms to solve the persistent Almajiri problems.

But reforming the Almajiri system is not a novel endeavour. The late General Hassan Usman Katsina acknowledged the need for a more inclusive and reorganised educational approach as early as the 1970s. His method sought to incorporate Western education into the Islamic curriculum as it was traditionally taught. The goal was to provide kids a well-rounded, holistic education by giving them the reading and numeracy skills they needed in the modern world, in addition to religious understanding.

Regretfully, local communities and traditional religious experts fiercely opposed these early reforms, believing that they would jeopardise long-standing social norms and religious traditions.

A few decades later, the Almajiri Education Programme, started by former President Goodluck Jonathan between 2010 and 2015, was a more structured effort. Through the establishment of 157 Tsangaya (Almajiri) Model Schools nationwide, this ambitious federal effort aimed to combine Islamic and secular education. In April 2012, the first of these schools was opened in Gagi, Sokoto State. Giving Almajiri youngsters access to formal education without sacrificing their Islamic studies was the explicit goal. However, because of poor administration, lack of sustainability, and inadequate follow-up, many of the schools have now been closed or allowed to deteriorate despite the large financial outlay and the symbolic promise of these establishments.

The reasons for constant failure of the Almajiri reforms are complex and rooted in structural, cultural, and social challenges.

Religious and cultural scepticism about including secular courses into Islamic education has been the biggest obstacle to reform. A lot of people in Northern Nigeria believe that the Almajiri system is a holy custom that shouldn’t be “corrupted” by debased Western norms. Any attempt to include formal education is frequently viewed as an infringement that compromises religious purity.

The insufficient involvement of local stakeholders, including parents, religious leaders, and traditional rulers, in the development and execution of changes was one of the major errors of previous reform initiatives. The programmes lacked credibility and ownership without their support, which led to minimal participation and little effect.

Many schemes, such as the model schools of the President Jonathan era were plagued by poor financing money, inadequate upkeep, and a shortage of qualified staff to manage them efficiently. Many of the facilities were left to deteriorate when the initial excitement subsided and the governments changed hands.

Reform initiatives have also been severely hampered by political inconsistency. Existing policies were abandoned or revised as a result of priorities changing with every change in leadership. Establishing and maintaining long-term initiatives that may have had a noticeable impact has been challenging due to this lack of stability.

In his administration’s attempt to successfully solve the Almajiri issue, Governor Ahmad Aliyu Sokoto seems to be taking a more nuanced and calculated approach after realising the historical mistakes of previous reform initiatives. His cooperation with the Sultanate Council, easily the most powerful religious organisations in Sokoto State, has been a noteworthy first step. His government hopes to gain support and legitimacy for changes by collaborating closely with well-respected religious leaders.

By supporting comprehensive education that incorporates both Islamic and formal subjects, the Sultanate may assist dispel cultural opposition and advance acceptance on a broad scale.

The policies of Governor Ahmad Aliyu place a strong emphasis on the value of including local populations in the planning and execution of educational reform, particularly parents and Islamic scholars. This inclusive strategy guarantees that changes are created in collaboration with people who will be most impacted, rather than being forced from the top down. Communities can be inspired to actively participate in maintaining educational projects and develop a feeling of ownership via such participation.

Through the State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), the Sokoto State Administration is promoting the reallocation of funds from higher education to foundational education in a daring but calculated move.

The government of Governor Aliyu understands that early childhood and basic education are the first steps towards long-term societal change. Every kid, including those in the Almajiri system, may have a solid educational foundation if the state makes investments in basic education curriculum development, teacher training, and infrastructure.

Additionally, the government has looked at potential international cooperation. Notably, throughout the previous five years, the Hungarian government has contributed more than $1 million to Sokoto’s main industries: agriculture, healthcare, and education. In addition to offering financial assistance, these multinational collaborations also bring in technology, knowledge, and best practices from throughout the world, all of which may help the state’s education system flourish.

The administration of Governor Aliyu Sokoto is encouraging skill development and entrepreneurial training since it understands that not all Almajiri children would pursue an academic career. This strategy is demonstrated by a recent programme that provides vocational training to 4,700 Almajiri teenage females. By teaching them useful skills in trades like computer technology, carpentry, and tailoring, these programmes help kids become less dependent on street begging and improve their prospects of being financially independent.

Governor Aliyu is promoting the creation and application of transparent, long-term policies that are impervious to political shifts in order to guarantee the durability of reforms. Notwithstanding future changes in leadership, putting these principles into place helps protect advancements and keep reform initiatives moving forward.

It is necessary to improve and modernise the Almajiri system, which has a rich cultural and religious legacy, rather than to destroy it. The government of Governor Ahmad Aliyu is at a turning point in history when lessons learnt from previous failures may guide a more sustainable and successful future.

Sokoto State can serve as a model for Almajiri reform in Nigeria by establishing solid alliances, including communities, directing resources where they are most needed, and maintaining policy continuity.

For thousands of children who deserve a chance at a better life, addressing the Almajiri crisis is about social fairness, opportunity, and dignity. It’s not just about education. The goal of an inclusive, practical, and caring educational system in Sokoto and, therefore, Northern Nigeria can be realised with the correct tactics and persistent dedication.

Gatekeepers News is not liable for opinions expressed in this article, they’re strictly the writer’s