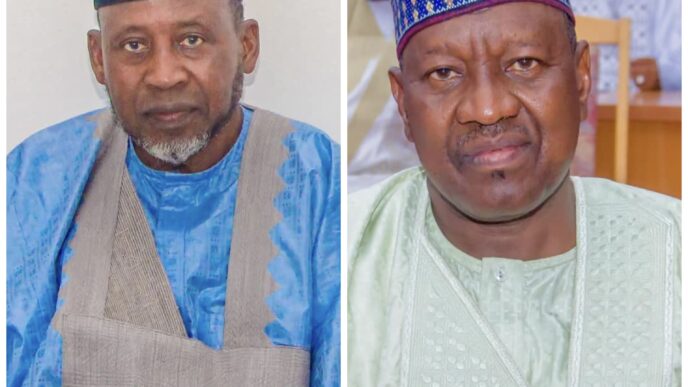

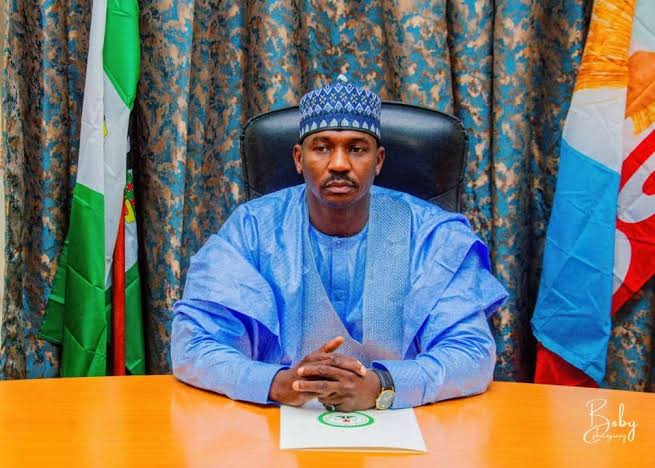

The Mesopotamians and Egyptians may lay claim to the world’s first irrigation systems, but in the 21st century, Sokoto State is rewriting that history in its own semi-arid terrain. Under Governor Ahmed Aliyu, the state is turning water, land, and trade into instruments of economic reinvention. The governor’s determined focus on agro-irrigation, value-chain development, and export-oriented farming signals a decisive break from the state’s long dependence on subsistence agriculture.

Agriculture remains Sokoto’s economic backbone. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the sector contributes roughly 42 percent of the state’s GDP, with over 70 percent of its population engaged in farming. Yet less than five percent of produce currently enters export channels. Governor Aliyu’s agricultural transformation plan—a key pillar of his nine-point “SMART Agenda”—aims to change that through innovation, commercialization, and value addition.

At the heart of this strategy is the 450-hectare Kware Irrigation Scheme, originally built in 1954 but left moribund for several decades. The project has now been rehabilitated and expanded to support year-round cultivation of rice, onions, and vegetables. Officials estimate annual yields of over 6,000 metric tons of rice and 5,000 metric tons of onions, providing food security while generating income for thousands of households. Beyond crop production, the scheme includes desilting of Kware Lake, construction of flood-control dykes, and a small-town water supply network for Kware and Durbawa communities.For many local farmers, the changes are tangible. “Before now, we could only plant during the rains. Now our farms stay green all year,” says Fatima Musa, a rice grower in Kware. “It means more food for our families and steady income for women farmers.”

The state’s agricultural vision is not merely about feeding its people, but also positioning Sokoto State as a credible agro-export hub. Though landlocked, Sokoto’s geography is strategic, it shares borders with Niger Republic and sits close to the trade corridors leading to Burkina Faso and other Sahelian economies. Experts note that with regional integration under ECOWAS and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Sokoto State can export produce through improved road networks and air freight. The state already sells cement to Niger and Burkina Faso via road—a template now being adapted for onions, rice, and processed moringa products. For non-perishable goods such as grains, the plan is to link Sokoto’s road networks to major West African ports in Togo, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire for onward shipment. For high-value or perishable products like fresh vegetables and onion flakes, air freight will provide quicker access to international markets. Governor Aliyu’s administration is partnering with specialized freight forwarders and logistics firms that manage cold-chain systems, to ensure that produce meets international freshness and safety standards.

One of the major flaws of Nigeria’s agricultural export system has been the dominance of raw, unprocessed exports. Sokoto State is breaking that pattern. The state is investing in processing and packaging facilities to extend shelf life, reduce spoilage, and meet the strict residue and quality standards required for international trade. For example, processing onions into flakes or powder would significantly reduce post-harvest losses and allow shipping by sea without compromising quality. These facilities will also create local jobs, as packaging and labeling operations expand. To support exporters, the government is establishing an Export Processing Zone in partnership with federal agencies. A newly launched “One-Stop Export Office” has now brought the Nigerian Export Promotion Council (NEPC), Standards Organisation of Nigeria (SON), NAFDAC, and the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) under one roof, easing regulatory compliance and documentation for businesses. Complementary infrastructure is also taking shape, the new Onion and Garlic Market Complex will streamline produce collection, improve quality control, and reduce waste before transport.

Any serious agricultural agenda in the 21st century must confront the climate change crisis. Sokoto’s semi-arid ecology faces erratic rainfall, desert encroachment, and heat stress, factors that can undo the gains recorded unless mitigated. Governor Aliyu’s team has therefore integrated climate-smart agriculture policies into its plans. Solar-powered pumps are being deployed across irrigation sites to reduce dependence on diesel, while farmers are being trained in the use of drought-tolerant seed varieties and organic fertilizers. The state has also begun pilot schemes on moringa agro-forestry, a dual-purpose model that improves soil fertility and provides exportable leaf and oil products. According to Dr. Halima Dan-Sani, an agricultural economist at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, “Sokoto’s approach of combining irrigation revival with renewable energy and agro-processing is one of the most comprehensive plan that we’ve seen in northern Nigeria. It addresses both productivity and sustainability.”

Critics often question whether Sokoto’s infrastructure can sustain such export ambitions. The governor’s response has been pragmatic: parallel investment in road networks, water systems, and logistics. The ongoing Kware–Illela road rehabilitation improves access to border points, while plans for a modern air cargo terminal at the Sokoto International Airport are being discussed with private investors. The state is also working with the Nigerian Shippers Council and NEXIM Bank to facilitate export financing and reduce logistics bottlenecks. Nevertheless, challenges persist particularly insecurity in parts of the northwest and instability in neighboring Sahel states. While recent geopolitical shifts in Niger and Burkina Faso have disrupted trade flows, historical and cultural ties between Sokoto and its neighbors remain strong. Analysts believe these can be leveraged to sustain cross-border commerce under new regional arrangements.

The potential economic impact of Governor Aliyu’s agricultural transformation is significant. Preliminary projections from the state’s economic planning office suggests that expanded irrigation and processing zones could create over 10,000 direct jobs and inject ₦15–20 billion annually into the state’s economy within the next five years. Beyond numbers, the social inclusion component is equally crucial. Women and youth are central to Sokoto’s agro-value chain—from production to processing. Through training programmes and cooperatives, the government aims to ensure that smallholders are not left behind in the transition to commercial farming. “The difference now,” says Malam Bello Sani, a youth cooperative leader in Goronyo, “is that we see ourselves as entrepreneurs, not just farmers. We can process, package, and sell—even across borders.”

Governor Aliyu’s professional background as a certified accountant is shaping his governance philosophy. His policies are data-driven, emphasizing measurable impact rather than political optics. Each agricultural intervention policy is monitored through key performance indicators, the hectares under irrigation, tonnage produced, jobs created, and export revenue generated. This analytical approach marks a shift from the rhetoric of previous agricultural campaigns. It embeds accountability in policy design which also help attract investment as the government has shown agriculture as a bankable business, and not merely a social sector.

Still, the road ahead will not be without hurdles. Climate volatility, market fluctuations, and global trade barriers remain formidable. The success of Sokoto’s export push will depend on how effectively it sustains infrastructure maintenance, farmer training, and policy consistency beyond the current administration. Experts also warn that regional insecurity could disrupt logistics, while access to affordable financing for small farmers remains limited. The state’s partnerships with commercial banks and agricultural development programmes will need to scale up to meet demand.

To consolidate its early progress, Sokoto State must now deepen private-sector participation. Encouraging agribusiness investors through tax incentives, access to land, and export guarantees will be critical. The establishment of the EPZ should go hand-in-hand with investment in warehousing, certification laboratories, and digital traceability systems that enhance export credibility. Furthermore, integrating climate insurance schemes and sustainable water-use policies will protect both farmers and the environment. Collaboration with research institutions like the Institute for Agricultural Research, Zaria, and international agencies such as FAO and USAID Feed the Future can bring new technologies and global best practices.

Sokoto’s agricultural renaissance under Governor Ahmed Aliyu is more than a state programme it is an economic reawakening. By marrying irrigation revival with value addition, logistics reform, and sustainability, the state is demonstrating that even in Nigeria’s driest zones, innovation can unlock abundance. If sustained, these reforms would make Sokoto State not only a breadbasket for Nigeria’s northwest but also a recognizable name in West African and global agro-exports. In Ghana and Togo, Sokoto onions is already a known brand. The challenge now is to ensure that every farmer, trader, and entrepreneur tremendously benefits from the transformation.Knowing Governor Ahmed Aliyu, that is the ultimate goal.

Gatekeepers News is not liable for opinions expressed in this article, they’re strictly the writer’s.