Introduction

Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country and the continent’s largest economy. By 2030 the global order will be more multipolar and unpredictable. Geopolitical competition among the United States, China, Europe and Russia has disrupted trade corridors and weaponised food, energy and finance. Climate change, the RussiaUkraine war and conflicts in the Sahel have exposed the limits of the old rulesbased system. In late 2025 this shifting landscape produced a jolt: United States President Donald Trump redesignated Nigeria a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) for “particularly severe violations of religious freedom,” threatened to cut aid and floated the possibility of military action if Nigeria failed to protect Christians. The label, which reverses the Biden administration’s 2021 delisting, raised questions about Nigeria’s ability to protect citizens and highlighted the absence of ambassadors to manage the fallout. Against this backdrop, Nigeria’s foreign policy cannot remain static. It must align domestic development with external engagement, protect national interests and project Nigeria’s voice in a fracturing world.

Legacy and the Need for Change

After independence Nigeria’s diplomacy rested on four ideas: Africa as the centrepiece, nonalignment, economic diplomacy and faith in multilateralism. These principles delivered liberation diplomacy in the 1970s and peacekeeping in Liberia and Sierra Leone in the 1990s, but they are no longer sufficient. Domestic turbulence – insecurity, poverty, corruption and climate shocks – has weakened Nigeria’s ability to achieve national goals. Scholars note that the country’s foreign policy has often been driven more by the personality of leaders than by coherent institutions. This inconsistency, coupled with poor coordination among ministries and overlapping mandates in climate and energy policy, dilutes Nigeria’s international messaging. A credible foreign policy must now address domestic resilience, reflect a multipolar world and harness Nigeria’s latent strengths.

Strategic Autonomy and the “4Ds”

Ambassador Yusuf Maitama Tuggar, Nigeria’s foreign minister, argues that foreign policy must be anchored on strategic autonomy and four pillars known as the 4Ds – Democracy, Development, Demography and Diaspora. Democracy is presented as the path to peace and a qualification for membership in influential groups. Development means deploying diplomacy to achieve doubledigit growth by combining agriculture, infrastructure and industrialisation; as Tuggar notes, “no electricity, no development”. Demography is viewed as an asset – Nigeria’s population is around 220 million and projected to become the thirdlargest nation by 2050. Finally, the diaspora, whose remittances reached $19.5 billion in 2023 (35 % of SubSaharan Africa’s total), is celebrated as a source of soft power and capital. These pillars align with Nigeria’s broader quest for strategic autonomy – engaging all global powers while avoiding subservience and maintaining an African voice. Tuggar’s framework emphasises active diplomacy over passivity, shifting Nigeria from a “bigbrother” myth to a disciplined power with a clear agenda.

Economic Diplomacy: Diversify or Decline

Nigeria’s economy remains heavily reliant on oil and gas, yet the petroleum sector now contributes less to growth than manufacturing and trade. McKinsey projections suggest that Nigeria could be among the world’s top 20 economies by 2030 if it sustains 7.1 % annual growth, lifting GDP to $1.6 trillion. However, these gains are conditional on execution—addressing poverty, reducing basic costs, expanding electricity and boosting farm productivity. Failure to diversify leads to stagnation: under a “Stagnation” scenario, Nigeria’s growth averages only 2.5 % a year and the economy remains vulnerable to commodity shocks because it fails to wean itself off oil. Infrastructure projects, such as railway lines between LagosKano and LagosCalabar, stagnate while offshoots of Boko Haram persist. Such an outcome keeps Nigeria stable but underperforming; it wastes its demographic dividend and leaves the country dependent on Chinese loans.

Actionable direction: Economic diplomacy must prioritise diversification. Nigeria should leverage the African Continental Free Trade Area to become a regional manufacturing hub. Gas pipelines – such as the TransSaharan Gas Pipeline and the NigeriaMorocco Gas Pipeline – could diversify Europe’s energy supply and symbolise Nigeria’s role in a new global order. But gas exports must be balanced with a plan for renewable energy and electrification, aligning with Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan and climate commitments. A coherent foreign policy can attract climate finance and technology partnerships while ensuring naturalgas projects support domestic electrification.

Nigeria should also embrace its digital economy. Lagos has been recognised as the world’s top emerging tech hub. The city’s booming technology and entertainment industries could make it Africa’s cultural and economic capital by 2030, surpassing Johannesburg. Diplomacy should therefore advocate fair rules for digital trade and data governance, resisting digital colonisation by either Western or Eastern powers.

Harnessing the Diaspora

Diaspora remittances are an economic lifeline. Nigeria received $19.5 billion from its diaspora in 2023 and is projected to receive $26 billion by 2025. These inflows represent around 80 % of the federal budget and exceed combined foreign direct investment and aid. Policies that integrate diaspora capital through transparent investment vehicles—diaspora bonds, digital savings accounts and diasporafocused real estate funds—can augment foreign reserves and support infrastructure. Additionally, the diaspora’s expertise enhances Nigeria’s soft power. A new foreign policy should institutionalise diaspora engagement in decisionmaking and use diplomatic missions to support overseas Nigerians.

Security and Regional Stability

Nigeria’s security challenges have regional implications. Terrorism, banditry and piracy undermine development and deter investment. Under President Tinubu, Nigeria’s Deep Blue Project has eliminated piracy incidents in its territorial waters, demonstrating effective maritime security when domestic and regional coordination align. But Boko Haram and its offshoots continue to threaten the northeast. The failure to address insecurity fuels fragmentation: an “Fragmentation” scenario sees Nigeria enter 2030 as a failed state where government control shrinks to major cities, secessionist movements proliferate and poverty and conflict are worse than at any time since the civil war. A de facto Biafran state emerges, Chinese firms dominate the depleted oil industry and foreign investment collapses.

Actionable direction: Nigeria must invest in cooperative security within ECOWAS, leveraging the Multinational Joint Task Force and other regional mechanisms to defeat insurgencies. The country should domesticate weapons production and maintain a strong defence capability to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers. Diplomatically, Nigeria should champion democratic governance in West Africa. Tuggar argues that mature democracies are less prone to conflict and more likely to promote human rights. Nigeria’s leadership in ECOWAS during the Niger coup crisis showed the tension between intervention and domestic opinion. A new policy must combine principled defence of constitutional order with sensitivity to cultural affinities to avoid alienating neighbouring populations.

Sponsored terrorism, mercenaries and defence autonomy

Nigeria’s security woes are not purely domestic. Criminal networks across the Middle East and Europe have financed militant groups. In 2022 the U.S. Treasury sanctioned six men in the United Arab Emirates for running a Boko Haram finance cell; they moved nearly $782 000 from Dubai to Boko Haram operatives in Nigeria. This shows that violent groups benefit from foreign sponsors. Diplomacy should focus on financial intelligence cooperation and insist that partners shut down these networks.

Calls for private armies must be resisted. In the Central African Republic, Mali and Mozambique, governments have hired foreign mercenaries such as the Russianlinked Wagner Group. Analysts warn that these companies are marketdriven and profit from conflict; they commit humanrights abuses and undermine sovereignty. In Mozambique, both mercenaries and local forces engaged in arbitrary arrests, abductions and extrajudicial killings while battling insurgents. In Mali, inviting the Wagner Group caused a surge in civilian deaths and diverted arms intended for the national army to the mercenaries. The United Nations working group on mercenaries warns that private military companies escape accountability and undermine treaties. If Nigeria were to hire mercenaries, it could fuel new forms of dependence and trigger fresh independence struggles. A principled nonaligned stance should therefore include an African consensus against mercenary deployment.

Instead, Nigeria should develop its own militaryindustrial complex. The Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria (DICON) has resumed ammunition production and, under a 2023 law, can operate subsidiaries and ordnance factories. The National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure describes the militaryindustrial complex as a national imperative that will design, produce and maintain equipment ranging from small arms to unmanned aerial vehicles. Under President Tinubu, DICON is setting up automated lines to produce drones, land vehicles and the BATA1 assault rifle. A recent $2 billion joint venture with SP Offshore Nigeria aims to manufacture drones and advanced munitions locally. Nigeria is also partnering with India to achieve 40% selfsufficiency in defence manufacturing within three years. Investing in domestic arms production reduces reliance on foreign suppliers, creates jobs and can position Nigeria as a regional defence supplier. Foreign partnerships should prioritise technology transfer and joint ventures that strengthen Nigeria’s industrial base.

Deciding who to align with should therefore account for security. Countries that fund violent extremists or rely on mercenaries should not be privileged partners. A robust militaryindustrial complex will give Nigeria leverage in negotiations and reduce dependence on any single foreign power. Rejecting mercenary forces and building local capacity will help prevent new cycles of domination and uphold Nigeria’s sovereignty.

Climate Diplomacy and Energy Transition

Nigeria has vowed to make climate advocacy central to foreign policy and created a special envoy and presidential climate committee, yet its governance is fragmented by overlapping mandates and misaligned energy laws. The country holds around 200 trillion cubic feet of gas, an asset that could light homes and earn foreign exchange, but the longterm goal remains to electrify Nigeria with renewables and build resilience.

Africa emits less than 4 % of global greenhouse gases yet bears the heaviest burden of climate impacts; wealthy nations promised $100 billion a year in climate finance but Africa receives less than 10 % of that. The continent holds nearly 30 % of the minerals needed for green technology, but only about 2 % of international cleanenergy investment flows there and 600 million Africans still lack electricity. Highincome countries built their wealth by burning fossil fuels and now account for almost half of historical emissions. While they lecture Africa on clean energy, they continue drilling: Canada remains the only G7 nation whose emissions are still above 1990 levels and has taken over the Trans Mountain pipeline to export record volumes of oil. Wealthy nations including the US, UK, Canada, Norway and Australia are responsible for more than twothirds of new oil and gas licences issued since 2020; under President Biden the US has issued 1,453 new licences—half of the global total and more than during Donald Trump’s term. This surge will unleash nearly 12 billion tonnes of greenhousegas emissions. The hypocrisy is clear: the same countries demanding rapid decarbonisation from Africa are expanding their fossilfuel frontiers.

African leaders are pushing back. Reports by the Tony Blair Institute argue that highincome countries have the greatest responsibility to cut emissions because twothirds of manmade carbon comes from them. They caution that expecting Africa to prioritise carbon reduction above domestic competitiveness is unrealistic; Africa’s industrial revolution will require a step change in climate finance and partnerships. The African Energy Chamber notes that even some African lobbyists have proposed a 30year phaseout of fossil fuels but warns that arbitrary deadlines threaten to entrench energy poverty. Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan estimates that reaching net zero by 2060 will cost around $410 billion. Without significant investment, phasing out oil and gas too quickly would stunt development.

Actionable direction: Nigeria should support ambitious climate action but insist on climate justice. Its diplomats should argue for a 29year transitional window—to 2054—that allows African countries to monetise gas and oil resources to fund a green industrial revolution, as long asrevenues are invested in renewable energy, electrification and adaptation. They must expose the double standards of countries that expand fossilfuel extraction while policing Africa’s energy choices. In multilateral forums such as BRICS+, the G77 and COP meetings, Nigeria should demand that wealthy nations fulfil their $100 billion finance pledge, provide technology transfer and open markets for African green products. Domestically, Nigeria should integrate climate objectives into all negotiations: adopt clear policies on gas flaring, hydrogen development and renewables, require climate expertise in its embassies and use gas revenues to fund a just transition. By championing a pragmatic, timebound approach, Nigeria can align its energy transition with its development goals and give substance to its nonaligned diplomacy.

NonAlignment and Strategic Partnerships

Global politics is no longer bipolar. The U.S., China and Russia each seek influence in Africa, often through economic or security dependencies. Ademola Oshodi argues for a principled nonalignment: Africa should resist being drawn into greatpower camps and instead assert strategic autonomy. For Nigeria, nonalignment means hedging, negotiating from strength and rejecting zerosum alignments. It requires leading an independent African digital sovereignty agenda, setting standards on artificial intelligence and data protection. Nigeria’s entry into BRICS+ provides a platform to push for IMF and WTO reforms, permanent African seats on the UN Security Council and equitable rules for climate finance. Aligning uncritically with any superpower narrows options and risks compromising institutions; a deliberate, autonomous approach maximises bargaining power.

Country of Particular Concern designation and diplomatic implications

Genesis of the CPC designation

On 31 October 2025 the United States redesignated Nigeria a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) under the International Religious Freedom Act. The White House said the Nigerian government was tolerating severe violations of religious freedom and President Donald Trump warned that the United States would cut aid and consider military action if “the killing of Christians” continued. The decision followed years of lobbying by U.S. congressmen, religiousfreedom activists and Nigerian bishops. At a March 2025 U.S. congressional hearing, Catholic Bishop Wilfred Anagbetestified that Fulani militias were raiding villages in Benue and other Middle Belt states, killing and kidnapping Christians with impunity while government forces looked away. Nina Shea’s Hudson Institute testimony argued that this selective nonresponse to Fulani militias—contrasted with an active fight against Boko Haram—met the CPC threshold because the state was “tolerating” the militias. Reports of mass killings in Taraba, Plateau and Benue states and appeals from religious activists culminated in Trump’s October announcement, which publicly acknowledged for the first time that Fulani militias were targeting Christians.

The redesignation was not unprecedented. Nigeria was first added to the CPC list in December 2020 during Trump’s first term and removed by the Biden administration in 2021. Its return to the list represented a sharp policy reversal and signalled U.S. impatience with Nigeria’s perceived inaction. U.S.–Nigeria relations, already strained by disagreements over security and immigration, deteriorated further as Trump threatened to cut aid and hinted at military intervention.

Nigeria’s response and global reactions

The Nigerian Ministry of Foreign Affairs rejected Trump’s allegations. In a statement issued on 1 November 2025 it insisted that religious freedom is not impeded in Nigeria and that Christians and Muslims have long lived and worshipped together. The ministry said the government remained committed to combating terrorism, fostering interfaith harmony and protecting citizens’ rights. It pledged to engage constructively with the U.S. government to improve mutual understanding of Nigeria’s security realities. Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar later argued that Nigeria’s diplomatic posture is rooted in strategic autonomy rather than hypocrisy; he warned against “bandwagoning” and declared that Nigeria’s foreign policy must evolve to meet a rapidly shifting global landscape.

International reactions were mixed. U.S. conservative groups applauded the designation, while analysts cautioned that oversimplifying Nigeria’s complex violence as solely Christian persecution misses governance failures and socioeconomic grievances. The Atlantic Council noted that the CPC label questioned Nigeria’s ability to protect citizens and widened the gap between Abuja and Washington. The United States is Nigeria’s largest foreign investor and bilateral trade exceeded $13 billion in 2024. Security cooperation includes military training, counterterrorism assistance and arms sales. A breakdown in relations therefore carries significant economic and security risks.

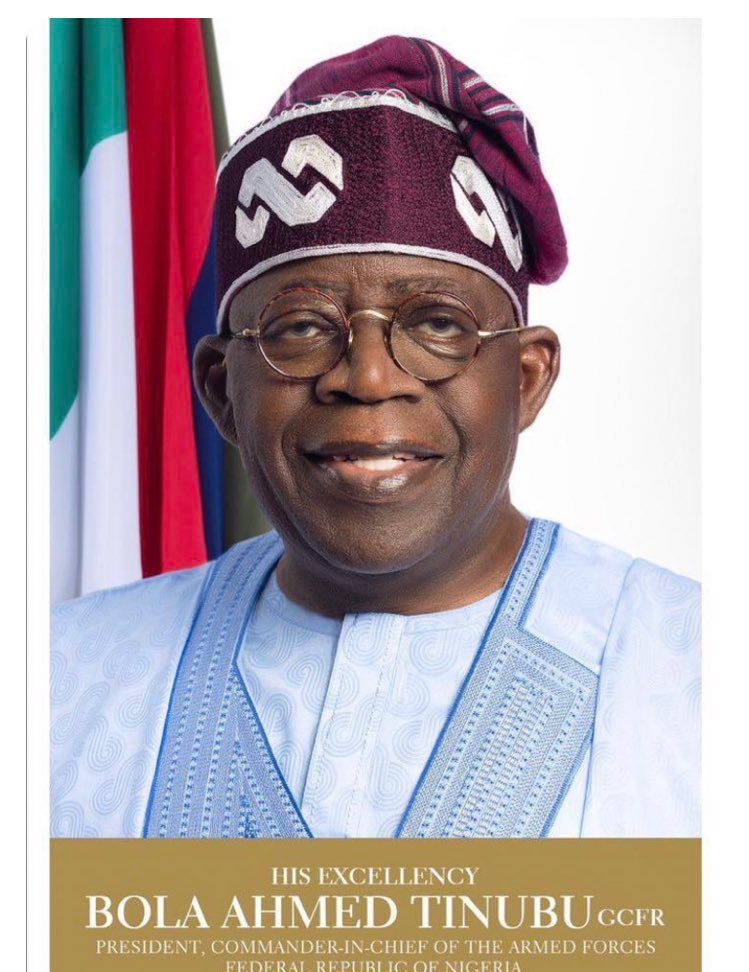

Diplomatic vacuum and ambassadorial appointments

The CPC crisis exposed a diplomatic vacuum. In September 2023 President Bola Tinubu recalled all Nigerian ambassadors and, for more than two years, failed to appoint replacements. Analysts and opposition parties warned that Nigeria lacked representation in key capitals and multilateral organisations, undermining its ability to respond to crises. Stakeholders at a Nigerian Institute of International Affairs roundtable described the situation as “the worst diplomatic lapse in the nation’s history” and urged the government to restore full representation. The African Democratic Congress (ADC) argued that the absence of ambassadors was damaging Nigeria’s global standing and delaying visa and consular services. Despite interim arrangements with chargés d’affaires, the vacuum left Nigeria unable to shape narratives or engage peers at the highest level.

On 29 November 2025 Tinubu finally sent the names of 32 ambassadorial nominees to the Senate for confirmation. The list includes 17 noncareer and 15 career diplomats. Notable noncareer nominees are former electoral commission chairman Mahmood Yakubu, former aviation minister Femi FaniKayode, former Enugu governor Ifeanyi Ugwuanyi, former presidential aide Reno Omokri and other politicians and technocrats. The career nominees include Enebechi Monica Okwuchukwu, Yakubu Nyaku Danladi and others. According to the presidency, these envoys will be posted to strategic countries such as China, India, South Korea, Canada, Mexico, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, South Africa, Kenya, and to permanent missions at the United Nations, UNESCO and the African Union. The nominations aim to fill vacancies created by the 2023 recall and restore Nigeria’s diplomatic reach.

However, critics argue that sending envoys without a clear foreign policy is a recipe for failure. Many of the nominees are political heavyweights rather than seasoned diplomats; without a coherent doctrine they may lack direction. The delay itself reflects deeper institutional weaknesses: Nigeria’s foreign policy often hinges on presidential preferences rather than longterm strategy. A revamped foreign policy should guide these envoys, offering clear priorities—strategic autonomy, economic diversification, climate diplomacy and nonalignment—so that Nigeria’s voice abroad is consistent and persuasive.

Implications for 2030 and beyond

If Nigeria uses the CPC designation as a wakeup call, it could overhaul its security sector, prosecute perpetrators of religious violence and rebuild trust with international partners. Constructive engagement with Washington might unlock targeted assistance for community policing and justice reforms. Combined with newly appointed ambassadors and a principled nonaligned strategy, Nigeria could reenter 2030 as a confident actor balancing relations with the U.S., China and other powers. Conversely, ignoring the designation invites sanctions, aid cuts and potential isolation. It could push Nigeria further into the orbit of alternative partners who might exploit its weaknesses and deepen dependency. Diplomatic inertia would also squander the opportunity to lead a NonAligned Movement 2.0. As Ademola Oshodi argues, Africa must practise nonalignment that is deliberate, discerning and diplomatically agile, hedging between greatpower blocs while asserting autonomy. For Nigeria, this means calibrating relations with the U.S. while maintaining ties with China and Russia, championing an independent digital and economic agenda, and pursuing reforms that protect human rights and religious freedom.

Consequences of Action and Inaction

The contrasting scenarios of Fragmentation, Stagnation and Emergence illustrate the stakes. In Fragmentation, Nigeria fails to reform, leading to secession, violence and economic collapse. In Stagnation, the country muddles through; growth remains low, infrastructure projects stall, insurgencies persist and China becomes the dominant investor. Only Emergence – a scenario driven by deep reforms, economic diversification and improved governance – sees Nigeria achieve 8 % annual growth, resolve internal conflicts, and become a great power in Africa. Lagos emerges as a cultural and economic capital, and Nigeria attracts diverse foreign investment and climbs toward highincome status. This outcome depends on sustained leadership, swift vaccination campaigns (as occurred in the scenario) and inclusive economic policies.

A new foreign policy can tip Nigeria toward the Emergence path. Without it, inertia could produce stagnation or fragmentation, leaving the nation vulnerable to external manipulation and domestic implosion.

Recommendations for Nigeria’s New Foreign Policy

Looking Beyond 2030

If Nigeria embraces a new foreign policy anchored in strategic autonomy, economic diversification, climate diplomacy and democratic values, it could emerge by 2030 as Africa’s leading power. The country has the demographic weight, cultural influence and resource endowments to become a global agendasetter. Conversely, failure to act will prolong stagnation or precipitate fragmentation. The choice is clear: Nigeria must seize this moment to reinvent its foreign policy and, in doing so, shape its destiny in the emerging world order.